Computers, the internet, and mobile phones brought transformative technological advancements: instant access to most of human knowledge; digital maps and navigation; and world wide real time communication.

They also brought many subtle improvements to our daily lives. Some advancements were so subtle that most people take them for granted.

This site explores one of those changes and what it was like pre-internet:

Knowing the Time

Be back by dark- 80s parents

Imagine you're a kid in the 80s out riding your bike with your friends. You likely didn't have a watch because they were too expensive. Your parents would tell you to be home by dark, or maybe when the street lights came on.

If you needed to be back at a specific time, so you would usually find some adult and ask:

Excuse me, do you have the time?

That was a relatively common expression back then. The expression is fading into obscurity now since most people just check their phone.

I just asked this to one of my kids and they responded with Time for what?”

Imagine further that there is a power outage at home and all your devices reset. The VCR is blinking 12:00. How do you know what time to set them to?

Needing an accurate time source to set watches and device in the home was a common problem. The solution was similar to the kids on the bikes. We would find, or actually, call, someone who knew the time.

In Northern California you could get the exact time by calling POP-CORN from your land line phone and a pre-recorded lady would read the time out to you.

The home page of this site simulates this experience. The history page documents my learnings and journey to finding the information necessary to create this site.

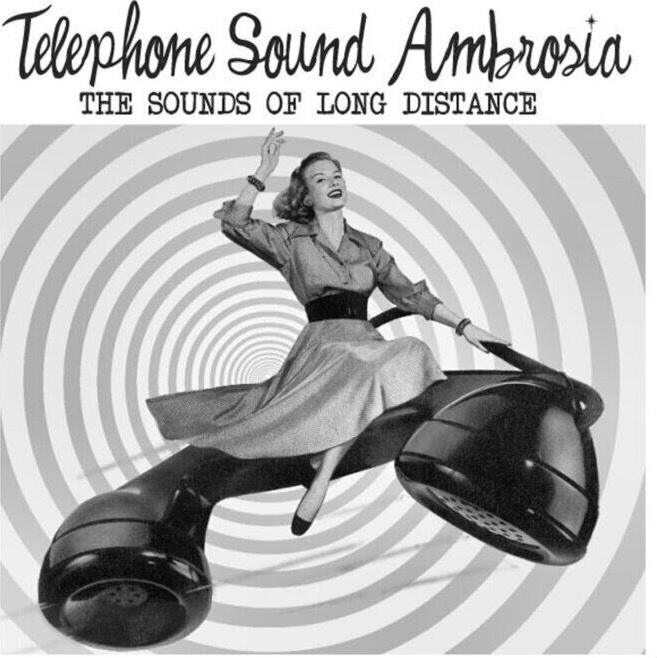

Phone companies around the country offered a similar "speaking clock" service. How did this work, and how did it come to be?

When the telephone system launched in 1878 people made calls by first connecting with the operator. They would provide the operator with the number of the person they were calling and the operator would manually connect them.

Note: this next section quotes/copies heavily from a

Bay Curious article in order to copy the quotes from their interview with with

Peter Amstein of the Telecommunications History Group

Operators had access to something the average person didn't in those days: the correct time.

Starting in 1870, Western Union, the telegraph company, offered a nationwide, highly accurate

time service, where they would install a clock in your business that was controlled centrally by

their master clock in New York City and represented super accurate time for the day,

explains

Peter Amstein of the Telecommunications History Group.

It's impossible for us to know exactly when someone first called the operator to ask her what

time it was,

says Amstein, but surely that happened in the very earliest days of the (phone)

system.

The phone company wanted to be friendly and helpful. And certainly if the operators weren't too busy and

had time,

they would answer all sorts of questions for people, like the weather and the current, correct time.

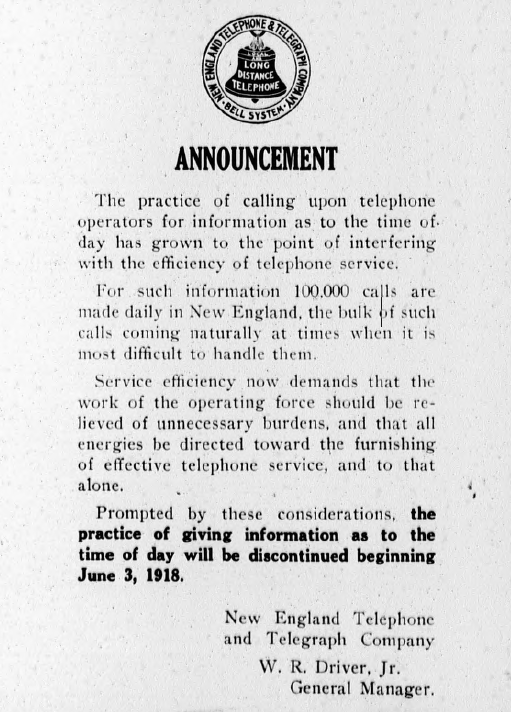

The phone company started putting notices in the newspaper that they would no longer respond to requests for information, and especially not requests for the time of day because it was interfering with their core business of connecting calls.

However, given the customer demand, some companies started offering a live time-of-day service where a live operator would read the time to callers.

In 1934,

says Amstein, a gentleman named John Franklin from Atlanta, Georgia, had the

brilliant idea to set up a phone number that people could call to hear the time that would

be sponsored by Tick Tock Ginger Ale.

To create his ad-supported call-in line, Franklin

repurposed an existing piece of phone company technology called a drum recorder.

A drum recorder uses a cylindrical drum coated in magnetic tape to record messages like, "The number you have dialed is no longer in service." Franklin reprogrammed the machine to play the current time, as read by an announcer. The company he created to sell that technology, Audichron, expanded into cities across the United States. The business model revolved around selling an ad, or the service and equipment themselves, to a sponsor. That advertiser could plug their company, and callers got the time and date. -- End of the quotes from Bay Curious

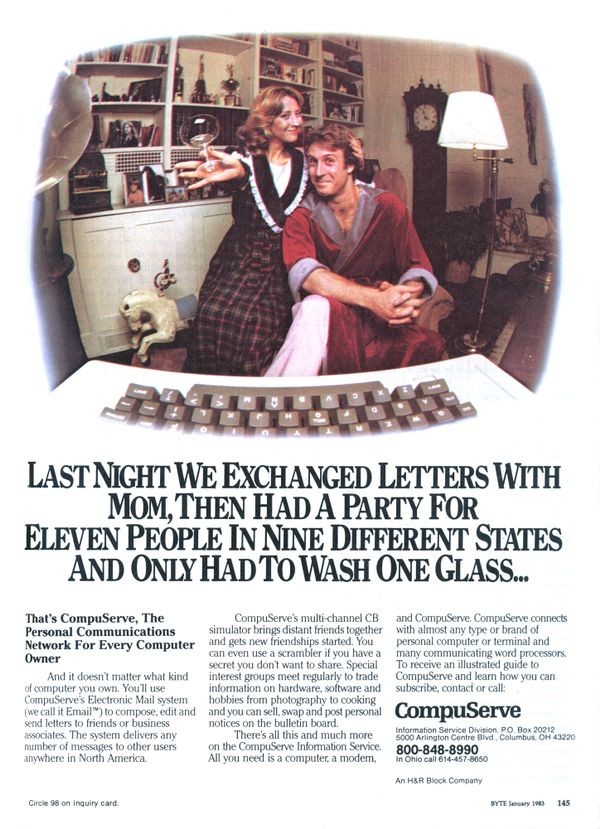

First online service

Compuserve, launched in 1969, is generally credited with being the first online service. However, in my opinion, Audichron and it's time service should receive this credit. While you may not have access its time service with a computer on the consumer side, you were accessing an automated source of information remotely. And, you did so “online” using the phone system, just as one did for Compuserve.

First online ad

I also find it amusing that this first online service was ads supported. John Franklin and Audichron set the stage for the monetization model for free online services.

As author Sonny Kleinfeld explained in his 1981 book The Biggest Company on Earth : A Profile of AT&T: Franklin shrewdly focused on an ads only business model:

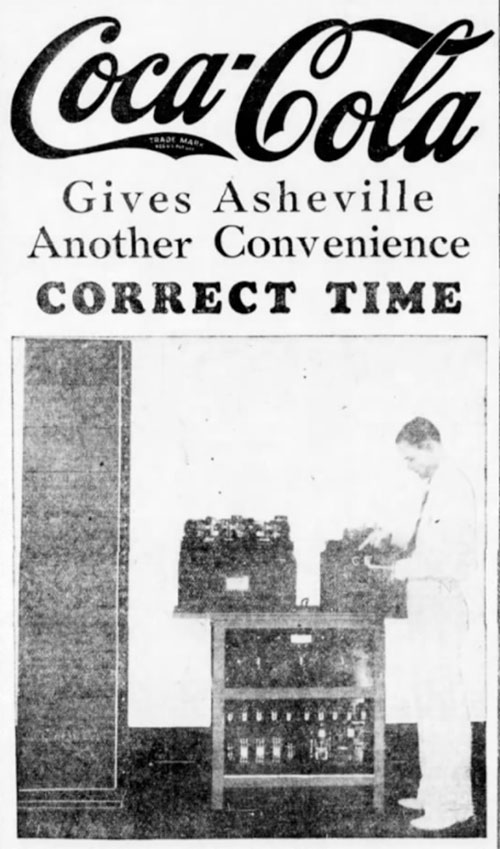

Initially, Franklin rented his time machines to local businesses. They would order additional phone lines

from the

phone company, hook up the time machines to them, and then devise promotional campaigns tied to the Time

of Day. One

of

Franklin's first clients was the Coca-Cola Company. The machines were an immediate hit, and Franklin had

no trouble

wooing an avalanche of customers. People called in swarms. It seemed that nobody knew what time it was.

Seeing all

this

action, the phone company shrewdly mentioned to Franklin that, by the way, it would be very happy to buy

his machines

and install them in its central offices.

Nope, nope, nope, Franklin said. He wasn't about to sell any of his time machines. He knew they were gold mines.

Kismet

I wasn't expecting online ads be to part of my journey in learning about POP-CORN. There is some major kismet at play here, as I led the engineering effort to build and and launch ads on Instagram.

Ironically the first ad featured a watch that was out of sync with the time described in the caption. If only they had called POP-CORN...

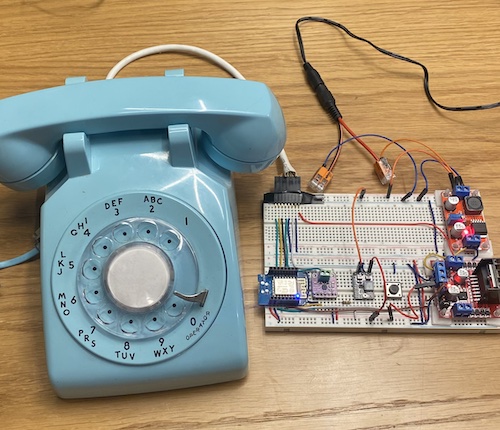

Recreating POP-CORN

I wanted to recreate the experience of physically dialing POP-CORN for nostalgia purposes. I have a working device that my kids love to play with as it has several other numbers you can call as well, eg 867-5309. 0, 411, etc.. This creation will be open soured with it's own technical writeup. In the mean time, enjoy the simulated experience here.

In order to recreate the POP-CORN experience, I needed to find source recordings with all versions of hour, minute, second, and other little phrases like, "at the tone the time will be.." I had a surprisingly hard time finding the complete Audichron source material.

There are many partial recordings of time services online. The site Telephone World has an impressive time collection of recordings from various regions. Unfortunately, they were only examples and didn't contain all the snippets to do a full reproduction.

Surely there must be some archive of these old systems. Where could I find it?

Phreaks to the rescue

The answer led me to trip down memory lane with the phone phreaks.

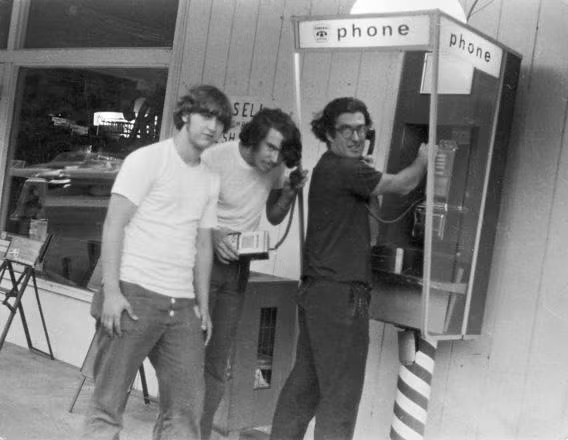

Back in the 70s and 80s there were people, mostly kids and young adults, known as “phone phreaks.” They were true hackers, in both senses of the word: they liked to tinker, explore, and ask the 'how and why' of technology; and they actually hacked into systems. They hacked the phone systems to get free long distance calls, hacked into corporate teleconferencing systems to setup free multi-way phone conferencing etc.

See the hacker's manifesto for a sense of the hacker ethos of the time. And Exploding the Phone for an in-depth dive into the storey of the phone phreaks.

While I had somewhat of a gray past myself from the early days of computers, BBBs, and the internet, I was only somewhat adjacent to phreak scene. While I used some of their tools here and there, I was basically the phone phreak equivalent of a script kiddie.

Documentarians

Since I wasn't really in the scene, I didn't know about the phone phreaks documentary work. It was amazingly thorough.

Evan Doorbell made a vast amount of documentary recordings of the phone system as it used to be in the 1970s, including interviews with famous phreaks, audio recordings of phreak conference calls and conventions, telephone technicians, telephone switching signaling, etc. There are hundreds, and possibly thousands, hours of material. He did a great service for those interest in telephone history.

I finally found what I was looking for deep in Evan

Doorbell's projection

tapes. Evan Doorbell made a full recording of an Audichron system in 1974. When I heard the intro:

This is a recording of an Audichron time announcing system with Jane Barbe's voice on it, in Greenville

North Carolina,

recorded locally in the same office...

-- I did a fist pump.

I used Audacity to cut up the sound file above into the necessary parts to recreate POP-CORN, including “at the tone the time will be”, each of the hour, minute and second readouts, plus “exactly” and “o'clock.”

I wrote a quick program on my computer to prototype timing and stitching the relevant pieces together. Jane started reading out the time to me. This was my first wave of real nostalgia.

I modified the program to work on a Western Electric Model 500 phone I bought on E-Bay. I called POP-CORN and Jane Barbe announced the current time. The nostalgia was complete.

I wanted to share the fun and nostalgia more broadly, and so, 7672676.io was born.

For those of you that are old enough to remember POP-CORN, I hope you find this as fun as I do. And for for both old and new alike, I hope you appreciate the conveniences of modern time keeping and it's history. Before I worked on this project, I was not as mindful that the ease of knowing the time is something I should be grateful for.

Enjoy.